What Was One of the First Cultures to Create Art for Pleasure?

In the years before World War I, Europe appeared to be losing its hold on reality. Einstein's universe seemed like science fiction, Freud'southward theories put reason in the grip of the unconscious and Marx's Communism aimed to turn lodge upside down, with the proletariat on superlative. The arts were besides coming unglued. Schoenberg'due south music was atonal, Mal-larmé's poems scrambled syntax and scattered words across the page and Picasso'southward Cubism made a hash of human being anatomy.

And even more radical ideas were afoot. Anarchists and nihilists inhabited the political fringe, and a new breed of artist was starting to attack the very concept of fine art itself. In Paris, subsequently trying his mitt at Impressionism and Cubism, Marcel Duchamp rejected all painting because it was made for the eye, not the mind.

"In 1913 I had the happy idea to fasten a cycle wheel to a kitchen stool and watch information technology turn," he subsequently wrote, describing the structure he called Cycle Wheel, a forerunner of both kinetic and conceptual fine art. In 1916, German author Hugo Ball, who had taken refuge from the war in neutral Switzerland, reflected on the state of contemporary art: "The prototype of the human grade is gradually disappearing from the painting of these times and all objects appear merely in fragments....The side by side step is for poetry to make up one's mind to do away with language."

That same yr, Ball recited just such a verse form on the stage of the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, a nightspot (named for the 18th-century French philosopher and satirist) that he, Emmy Hennings (a vocalist and poet he would later marry) and a few expatriate pals had opened equally a gathering place for artists and writers. The poem began: "gadji beri bimba / glandridi lauli lonni cadori...." It was utter nonsense, of course, aimed at a public that seemed all too complacent nigh a senseless war. Politicians of all stripes had proclaimed the war a noble cause—whether information technology was to defend Germany's high culture, France'due south Enlightenment or United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland's empire. Ball wanted to shock anyone, he wrote, who regarded "all this civilized carnage as a triumph of European intelligence." 1 Cabaret Voltaire performer, Romanian artist Tristan Tzara, described its nightly shows as "explosions of elective imbecility."

This new, irrational fine art move would exist named Dada. It got its name, co-ordinate to Richard Huelsenbeck, a German artist living in Zurich, when he and Ball came upon the word in a French-High german dictionary. To Brawl, information technology fit. "Dada is 'yes, aye' in Rumanian, 'rocking horse' and 'hobby equus caballus' in French," he noted in his diary. "For Germans it is a sign of foolish naiveté, joy in procreation, and preoccupation with the babe carriage." Tzara, who later claimed that he had coined the term, speedily used it on posters, put out the first Dada periodical and wrote i of the beginning of many Dada manifestoes, few of which, appropriately enough, fabricated much sense.

Just the absurdist outlook spread like a pandemic—Tzara called Dada "a virgin microbe"—and there were outbreaks from Berlin to Paris, New York and even Tokyo. And for all its zaniness, the movement would prove to be one of the most influential in modern fine art, foreshadowing abstruse and conceptual fine art, performance fine art, op, pop and installation art. Just Dada would die out in less than a decade and has not had the kind of major museum retrospective information technology deserves, until now.

The Dada exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (on view through May fourteen) presents some 400 paintings, sculptures, photographs, collages, prints, and movie and sound recordings by more than xl artists. The prove, which moves to New York's Museum of Modern Art (June 18 through September 11), is a variation on an even larger exhibition that opened at the Pompidou Center in Paris in the fall of 2005. In an effort to brand Dada easier to understand, the American curators, Leah Dickerman, of the National Gallery, and Anne Umland, of MoMA, accept organized it around the cities where the motility flourished—Zurich, Berlin, Hanover, Cologne, New York and Paris.

Dickerman traces Dada's origins to the Great War (1914-18), which left x one thousand thousand expressionless and some twenty million wounded. "For many intellectuals," she writes in the National Gallery catalog, "Globe War I produced a plummet of confidence in the rhetoric—if not the principles—of the culture of rationality that had prevailed in Europe since the Enlightenment." She goes on to quote Freud, who wrote that no event "dislocated so many of the clearest intelligences, or so thoroughly debased what is highest." Dada embraced and parodied that confusion. "Dada wished to supercede the logical nonsense of the men of today with an casuistic nonsense," wrote Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia, whose artist husband, Francis Picabia, once tacked a stuffed monkey to a lath and called it a portrait of Cézanne.

"Total pandemonium," wrote Hans Arp, a young Alsatian sculptor in Zurich, of the goings-on at the "gaudy, motley, overcrowded" Cabaret Voltaire. "Tzara is wiggling his behind similar the belly of an Oriental dancer. Janco is playing an invisible violin and bowing and scraping. Madame Hennings, with a Madonna face, is doing the splits. Huelsenbeck is banging away nonstop on the not bad drum, with Brawl accompanying him on the pianoforte, stake as a chalky ghost."

These antics struck the Dada crowd as no more absurd than the state of war itself. A swift German offensive in April 1917 left 120,000 French expressionless just 150 miles from Paris, and one hamlet witnessed a band of French infantrymen (sent equally reinforcements) baa-ing like lambs led to slaughter, in futile protestation, as they were marched to the forepart. "Without World War I in that location is no Dada," says Laurent Le Bon, the curator of the Pompidou Center's prove. "Simply there's a French saying, 'Dada explains the war more than the war explains Dada.'"

2 of Deutschland'south military leaders had dubbed the war "Materialschlacht," or "the battle of equipment." But the dadas, every bit they called themselves, begged to differ. "The war is based on a crass mistake," Hugo Brawl wrote in his diary on June 26, 1915. "Men accept been mistaken for machines."

It was non merely the war but the impact of modern media and the emerging industrial age of science and technology that provoked the Dada artists. As Arp once complained, "Today's representative of human being is but a tiny push on a giant senseless machine." The dadas mocked that dehumanization with elaborate pseudodiagrams—chockablock with gears, pulleys, dials, wheels, levers, pistons and clockworks—that explained nix. The typographer'south symbol of a pointing mitt appeared frequently in Dada art and became an emblem for the motility—making a pointless gesture. Arp created abstract compositions from cutout paper shapes, which he dropped randomly onto a background and glued down where they fell. He argued for this kind of chance abstraction as a mode to rid art of any subjectivity. Duchamp plant a different mode to make his art impersonal—drawing like a mechanical engineer rather than an artist. He preferred mechanical drawing, he said, considering "it'southward exterior all pictorial convention."

When Dadaists did choose to stand for the homo form, it was often mutilated or made to look manufactured or mechanical. The multitude of severely crippled veterans and the growth of a prosthetics manufacture, says curator Leah Dickerman, "struck contemporaries as creating a race of half-mechanical men." Berlin artist Raoul Hausmann made a Dada icon out of a wig-maker's dummy and various oddments—a crocodile-skin wallet, a ruler, the mechanism of a pocket watch—and titled it Mechanical Caput (The Spirit of Our Age). Two other Berlin artists, George Grosz and John Heartfield, turned a life-size tailor's dummy into a sculpture by adding a revolver, a doorbell, a knife and fork and a High german Army Iron Cantankerous; they gave it a working light seedling for a head, a pair of dentures at the crotch and a lamp stand up as an artificial leg.

Duchamp traced the roots of Dada's farcical spirit back to the 5th-century b.c. Greek satirical playwright Aristophanes, says the Pompidou Center's Le Bon. A more immediate source, however, was the absurdist French playwright Alfred Jarry, whose 1895 farce Ubu Roi (King Ubu) introduced "'Pataphysics"—"the science of imaginary solutions." Information technology was the kind of science that Dada applauded. Erik Satie, an avant-garde composer who collaborated with Picasso on stage productions and took part in Dada soirees, claimed that his audio collages—an orchestral suite with passages for piano and siren, for case—were "dominated by scientific thought."

Duchamp probably had the virtually success turning the tools of science into fine art. Built-in well-nigh Rouen in 1887, he had grown up in a bourgeois family that encouraged art—2 older brothers and his younger sis also became artists. His early paintings were influenced by Manet, Matisse and Picasso, but his Nude Descending a Staircase no. two (1912)—inspired by early stop-activeness photographic studies of motion—was entirely his own. In the painting, the female nude figure seems to accept on the anatomy of a machine.

Rejected by the jury for the Salon des Independants of 1912 in Paris, the painting created a awareness in America when information technology was exhibited in New York City at the 1913 Armory Show (the country'south get-go large-scale international exposition of modern fine art). Drawing parodies of the work appeared in local papers, and one critic mocked information technology equally "an explosion in a shingle factory." The Nude was snapped upwardly (for $240) by a collector, every bit were three other Duchamps. 2 years after the show, Duchamp and Picabia, whose paintings had also sold at the Armory Show, traded Paris for Manhattan. Duchamp filled his studio on West 67th Street with shop-bought objects that he called "readymades"—a snow shovel, a hatrack, a metallic dog comb. Explaining his selections some years later on, he said: "Yous have to approach something with an indifference, every bit if you had no aesthetic emotion. The selection of readymades is always based on visual indifference and, at the aforementioned fourth dimension, on the total absenteeism of proficient or bad taste." Duchamp didn't showroom his readymades at first, merely he saw in them notwithstanding another fashion to undermine conventional ideas about fine art.

In 1917, he bought a porcelain urinal at a Fifth Avenue plumbing supply store, titled it Fountain, signed it R. Mutt and submitted it to a Social club of Independent Artists exhibition in New York City. Some of the show's organizers were aghast ("the poor fellows couldn't sleep for 3 days," Duchamp afterward recalled), and the piece was rejected. Duchamp resigned as chairman of the exhibition commission in back up of Mutt and published a defense force of the piece of work. The ensuing publicity helped make Fountain i of Dada's most notorious symbols, along with the print of Leonardo da Vinci'due south Mona Lisa the following twelvemonth, to which Duchamp had added a penciled mustache and goatee.

Parodying the scientific method, Duchamp made voluminous notes, diagrams and studies for his almost enigmatic work, The Helpmate Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (or The Large Glass)—a nine-foot-tall aggregation of metal foil, wires, oil, varnish and dust, sandwiched betwixt glass panels. Art historian Michael Taylor describes the work every bit "a complex apologue of frustrated want in which the 9 uniformed bachelors in the lower panel are perpetually thwarted from copulating with the wasplike, biomechanical helpmate above."

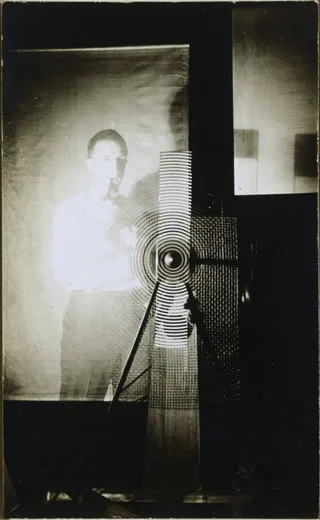

Duchamp's irreverence toward science was shared by two of his New York companions, Picabia and a young American photographer, Homo Ray. Picabia could depict with the precision of a commercial artist, making his nonsensical diagrams seem particularly convincing. While Duchamp built machines with spinning disks that created surprising spiral patterns, Picabia covered canvases with disorienting stripes and concentric circles—an early form of optical experimentation in mod painting. Man Ray, whose photographs documented Duchamp'due south optical machines, put his own stamp on photography past manipulating images in the darkroom to create illusions on film.

After the war ended in 1918, Dada disturbed the peace in Berlin, Cologne, Hanover and Paris. In Berlin, artist Hannah Höch gave an ironic domestic touch to Dada with collages that incorporated sewing patterns, cut-up photographs taken from mode magazines and images of a German military and industrial gild in ruins.

In Cologne, in 1920, High german creative person Max Ernst and a ring of local dadas, excluded from a museum exhibition, organized their own—"Dada Early Leap"—in the courtyard of a pub. Out past the men's room, a daughter wearing a "communion apparel recited lewd poetry, thus assaulting both the sanctity of high art and of religion," art historian Sabine Kriebel notes in the current exhibition'due south catalog. In the courtyard, "viewers were encouraged to destroy an Ernst sculpture, to which he had attached a hatchet." The Cologne police force shut downwardly the show, charging the artists with obscenity for a display of nudity. Simply the charge was dropped when the obscenity turned out to be a print of a 1504 engraving by Albrecht Dürer titled Adam and Eve, which Ernst had incorporated into 1 of his sculptures.

In Hanover, artist Kurt Schwitters began making art out of the detritus of postwar Germany. "Out of parsimony I took whatever I institute to do this," he wrote of the trash he picked up off the streets and turned into collages and sculptural assemblages. "One can even shout with reject, and this is what I did, nailing and gluing it together." Built-in the same year as Duchamp—1887—Schwitters had trained as a traditional painter and spent the war years as a mechanical draftsman in a local ironworks. At the state of war's end, however, he discovered the Dadaist movement, though he rejected the proper name Dada and came upward with his own, Merz, a word that he cut out of an advertizing poster for Hanover's Kommerz-und Privatbank (a commercial banking company) and glued into a collage. As the National Gallery's Dickerman points out, the give-and-take invoked not merely money just too the German word for pain, Schmerz, and the French word for excrement, merde. "A piffling coin, a little pain, a little sh-t," she says, "are the essence of Schwitters' fine art." The complimentary-course construction built out of found objects and geometric forms that the creative person called the Merzbau began as a couple of three-dimensional collages, or assemblages, and grew until his house had get a construction site of columns, niches and grottoes. In time, the sculpture actually broke through the building'south roof and outer walls; he was still working on information technology when he was forced to flee Germany past the Nazis' rise to power. In the end, the work was destroyed by Allied bombers during World War II.

Dada's last hurrah was sounded in Paris in the early 1920s, when Tzara, Ernst, Duchamp and other Dada pioneers took part in a series of exhibitions of provocative art, nude performances, rowdy stage productions and incomprehensible manifestoes. But the movement was falling apart. The French critic and poet André Breton issued his own Dada manifestoes, but fell to feuding with Tzara, every bit Picabia, fed up with all the infighting, fled the scene. Past the early 1920s Breton was already hatching the next great avant-garde thought, Surrealism. "Dada," he gloated, "very fortunately, is no longer an issue and its funeral, almost May 1921, caused no rioting."

But Dada, which wasn't quite dead all the same, would soon jump from the grave. Arp'south abstractions, Schwitters' constructions, Picabia's targets and stripes and Duchamp's readymades were before long turning up in the piece of work of major 20th-century artists and art movements. From Stuart Davis' abstractions to Andy Warhol's Pop Fine art, from Jasper Johns' targets and flags to Robert Rauschenberg's collages and combines—almost anywhere yous wait in modern and gimmicky art, Dada did it first. Even Breton, who died in 1966, recanted his disdain for Dada. "Fundamentally, since Dada," he wrote, not long before his death, "we have washed nada."

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/dada-115169154/

0 Response to "What Was One of the First Cultures to Create Art for Pleasure?"

Postar um comentário